Robert McKellar

At International Pulp Week, political risk expert Robert McKellar delivered a timely and unconventional keynote that used a real-world policy shift to test a scenario-based approach to geopolitical uncertainty. Titled “Managing Geopolitical Uncertainty and Its Challenges,” the presentation featured a hypothetical pulp company navigating a shifting landscape of US tariffs, culminating in an unexpected twist: a policy reversal on tariffs the day after the analysis was completed.

McKellar, Director of Harmattan Risk, emphasized from the outset that his session was not about delivering forecasts or policy advice, but about helping companies become more comfortable working with uncertainty. The tool he introduced—a scenario-based assessment—was less about pinpoint accuracy and more about creating a “living intelligence picture” to guide decisions in real time.

The unique twist, however, was that McKellar’s own process of preparing for the keynote presentation mimicked the very conditions of uncertainty he was seeking to illustrate. As he developed Thor Wood Pulp AB’s case study throughout late March and early April, the global trade landscape kept shifting. His assessment was finalized on April 8. On April 9, the Trump administration abruptly announced a 90-day pause on reciprocal tariffs. This reversal not only disrupted his planned narrative, but underscored his entire thesis: in volatile times, any analytical framework must remain adaptive, fluid, and responsive.

The unique twist, however, was that McKellar’s own process of preparing for the keynote presentation mimicked the very conditions of uncertainty he was seeking to illustrate. As he developed Thor Wood Pulp AB’s case study throughout late March and early April, the global trade landscape kept shifting. His assessment was finalized on April 8. On April 9, the Trump administration abruptly announced a 90-day pause on reciprocal tariffs. This reversal not only disrupted his planned narrative, but underscored his entire thesis: in volatile times, any analytical framework must remain adaptive, fluid, and responsive.

To make his message more concrete, McKellar introduced the fictional company Thor Wood Pulp AB, a mid-sized Scandinavian producer with a complex global footprint. Thor sources wood from Northern Europe and, until recently, Russia. Following the outbreak of the Ukraine conflict, it turned to the US to fill the supply gap. Its production inputs span the EU, China, and the US, and its major export markets include the EU, China, the US, India, and the Middle East.

On April 2, the Trump administration imposed sweeping reciprocal tariffs. For Thor, the implications were severe: its pulp exports to the US were now 30% more expensive, and its US-sourced wood was vulnerable to retaliatory measures from both the EU and China. As McKellar put it, Thor’s CEO was “tired of being surprised by political change.”

On April 2, the Trump administration imposed sweeping reciprocal tariffs. For Thor, the implications were severe: its pulp exports to the US were now 30% more expensive, and its US-sourced wood was vulnerable to retaliatory measures from both the EU and China. As McKellar put it, Thor’s CEO was “tired of being surprised by political change.”

Rather than respond instinctively, Thor’s planning team turned to scenario analysis. With a 1.5-year time horizon—unusually short for scenario work, but justified given the pace of change—they identified four key variables: Trump’s personal commitment to tariffs, his level of control over the US government, the economic effects of the tariffs domestically, and how major trading partners would respond.

These variables formed the basis for three plausible scenarios:

- Start with a Bang: The US uses high tariffs as a negotiating tool, leading to short-term shocks but eventual bilateral deals and easing.

- Melodrama: A cycle of aggressive tariff moves and subsequent pullbacks, reflecting internal tensions between Trump’s economic goals and political instincts.

- New World Order: A hard-line, long-term restructuring of global trade driven by unwavering commitment to tariffs, possibly linked to ambitions for a third Trump term.

While these scenarios were designed to help Thor plan, McKellar stressed they were only baselines. To avoid being blindsided, companies also needed to keep an eye on fringe possibilities. These included a sudden US-EU free trade agreement, an international crisis that forced a tariff delay, or Trump pivoting away from tariffs to focus on other foreign policy issues.

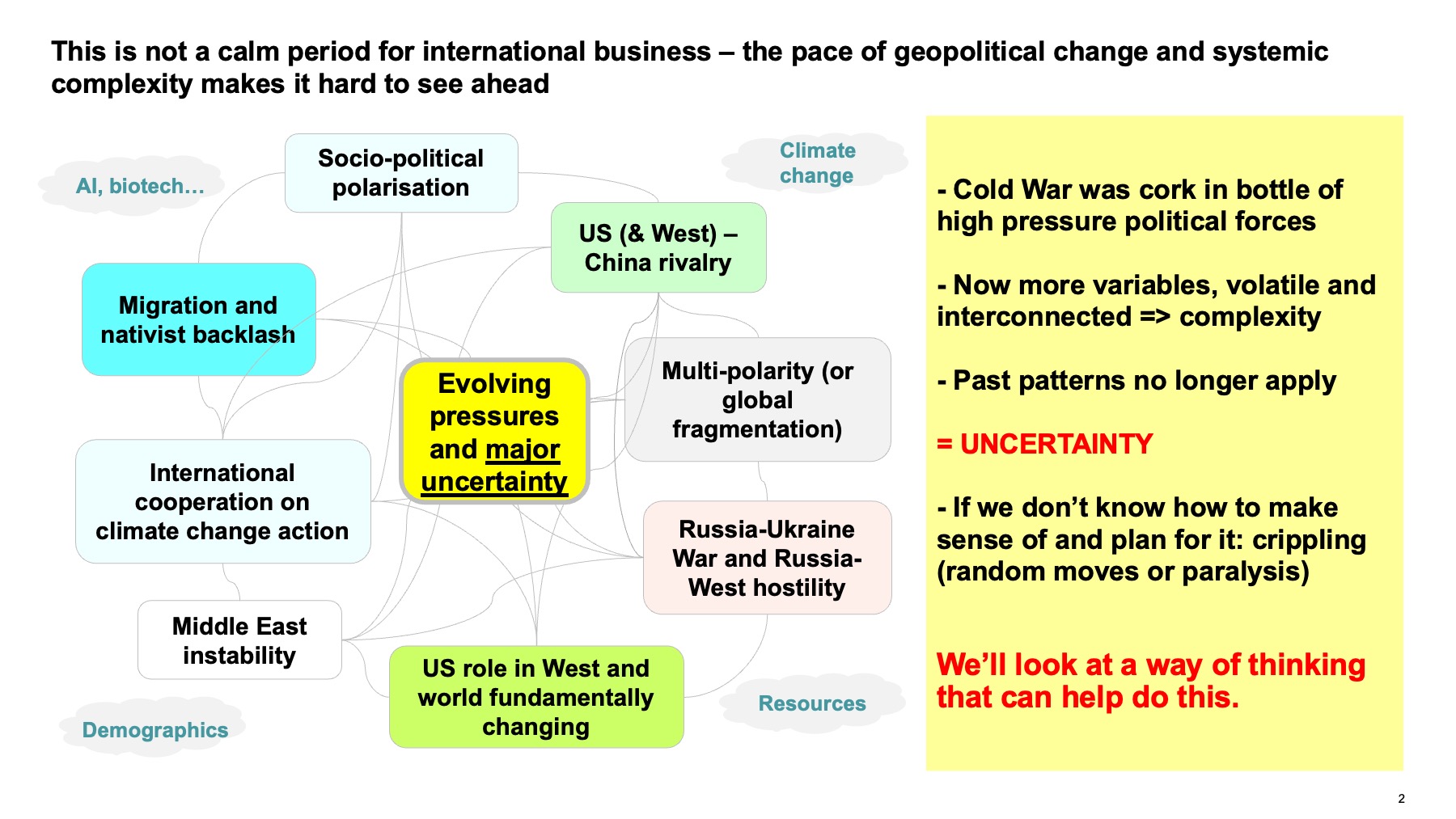

In outlining his method, McKellar also made a broader philosophical point: uncertainty today is structural, not cyclical. He traced this back to the Cold War era, describing it as a time when superpowers acted as stabilizing forces, effectively suppressing competing variables. Once that era ended, McKellar explained, a proliferation of competing identities, interests, and forces emerged, accelerated by globalization and digital connectivity. “Now, instead of a few clear paths, we face a tangle of interacting variables,” he said.

He also warned against two common but flawed reactions to this environment: paralysis and whiplash. “Some companies wait for clarity that never comes,” said McKellar. He contrasted this with firms that overreact to headlines, noting that both approaches can leave organizations misaligned with deeper global shifts.

Another key insight: leaders—especially in autocratic or highly personalized regimes—don’t think like analysts. “They have their own worldview, shaped by ideology, ambition, and ego,” said McKellar. “Political leaders aren’t analysts. They don’t think like economists, and their decisions are shaped by ideology and image.”

Another key insight: leaders—especially in autocratic or highly personalized regimes—don’t think like analysts. “They have their own worldview, shaped by ideology, ambition, and ego,” said McKellar. “Political leaders aren’t analysts. They don’t think like economists, and their decisions are shaped by ideology and image.”

And then, reality intervened. On April 9, the Trump administration announced a 90-day pause on most reciprocal tariffs. Far from invalidating the exercise, this development validated it. McKellar pointed out that the “Melodrama” scenario had anticipated a reactive, seesaw policy pattern. In addition, one of the fringe possibilities—Trump abandoning the tariff campaign in favour of a renewed focus on China—was now playing out in real time.

With the US-China rivalry intensifying, Thor’s team updated their approach. They now looked at global trade through a different lens: one shaped by the evolving dynamic between Washington and Beijing. McKellar outlined three new scenarios:

- Creeping Bifurcation: The world divides into US- and China-led trading blocs, with both sides applying pressure through tariffs and weakening financial ties.

- Deal then Fragile Stasis: A negotiated truce emerges, but is underpinned by mutual distrust and high, lingering tariffs.

- Rest of World Plays Both Sides: Other nations attempt to stay neutral, maintaining flexible trade relations while absorbing collateral damage from the great power rivalry.

Thor then revisited its initial US-focused scenarios to see how they held up under this new framework. “Start with a Bang” and “Melodrama” still held relevance, especially in understanding the US’s strategic calibration of pressure. But the “New World Order” scenario appeared increasingly untenable. Fighting simultaneous trade wars on multiple fronts was proving unsustainable for the US.

By mid-May, another insight surfaced. McKellar’s team noted that when US-China tensions escalated, the Trump administration tended to ease pressure on allies. But when US-China talks were more stable, pressure shifted back to the EU and others. This behavioural pattern became a “predictive tool” for Thor’s planners, enabling them to better anticipate future policy shifts.

By mid-May, another insight surfaced. McKellar’s team noted that when US-China tensions escalated, the Trump administration tended to ease pressure on allies. But when US-China talks were more stable, pressure shifted back to the EU and others. This behavioural pattern became a “predictive tool” for Thor’s planners, enabling them to better anticipate future policy shifts.

Based on this evolving picture, Thor made several pragmatic decisions. First, it shifted from US to Canadian wood, citing the risk of Chinese retaliation and the increased vulnerability of US content. Second, it accelerated efforts to expand into Asia and the Middle East—regions with growing demand and less direct exposure to tariff instability. Third, it began reducing its reliance on capital goods with joint US-China origins, identifying alternative supply chains where feasible.

None of these were transformative moves, but they were strategically sound. “Sometimes there’s a kick we need to actually start doing the things we’ve been procrastinating on,” McKellar remarked.

Another wrinkle soon emerged. A US court ruled that the administration’s reciprocal tariffs lacked legal basis, prompting more questions. Would the White House challenge the decision or seek an alternative legal pathway? Might executive powers be expanded to regain control of tariff authority?

Again, Thor’s team leaned on scenario thinking. They imagined themselves in the shoes of senior US policymakers, considering how they might respond. If tariffs were seen as central to the administration’s economic strategy, efforts to bypass or override the court ruling were likely.

For McKellar, the point was not to anticipate every detail, but to maintain alignment with evolving reality. “Assessment can be fast and crude,” he said. “Don’t be afraid to be wrong. The only wrong is attachment to intelligence that misaligns with reality.”

He warned against overly rigid strategy development. Even the most comprehensive plans must include flexible elements that can adapt as the landscape shifts. “Why look ahead when things change week by week?” he asked. “Try climbing a mountain looking only one foot ahead.”

During the Q&A, session moderator Kelly McNamara, director at Numera Analytics, asked McKellar whether the current climate of uncertainty was tied to the Trump administration or part of a broader structural shift. He reaffirmed his position: “Uncertainty is here to stay,” he said, citing long-term trends like fragmented global power, rapid technological shifts, and identity-driven politics. But he added that Trump introduces a distinctive form of volatility. “There are periods of history that are unique in the sense of personality. Trump’s up-and-down approach is uniquely destabilizing, even within the broader wave of nationalist politics.”

During the Q&A, session moderator Kelly McNamara, director at Numera Analytics, asked McKellar whether the current climate of uncertainty was tied to the Trump administration or part of a broader structural shift. He reaffirmed his position: “Uncertainty is here to stay,” he said, citing long-term trends like fragmented global power, rapid technological shifts, and identity-driven politics. But he added that Trump introduces a distinctive form of volatility. “There are periods of history that are unique in the sense of personality. Trump’s up-and-down approach is uniquely destabilizing, even within the broader wave of nationalist politics.”

Another question by McNamara focused on whether businesses need to hire outside political risk experts to build this kind of capacity. McKellar was optimistic: “The tools already exist inside most companies,” he said. “They just need to stretch their thinking to include variables they might not normally consider—like political leadership, negotiation styles, or national ideology.” He encouraged companies to involve younger or internationally experienced staff and to treat political risk analysis as a core business function, not an external add-on.

The session closed with a call to cultivate what McKellar called “garnered intelligence” — not just information collection, but the ability to distinguish what matters and act on it. “Events and information are transient,” he concluded. “What endures is the skill to make sense of it.”

His message was clear: in a world of rapid political change, pulp producers and global businesses don’t need perfect foresight. What they need is a way to stay balanced, make timely decisions, and keep moving forward—even when the path ahead is constantly shifting.