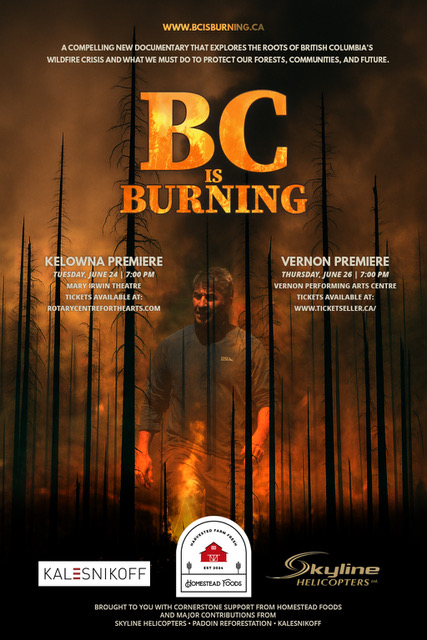

Day three of the Truck Loggers Association convention opened with a private screening of BC Is Burning, a documentary produced by professional forester Murray Wilson that examines the province’s escalating wildfire crisis and the forest-management choices shaping its severity. Introduced by moderator Vaughn Palmer as an “urgent, powerful documentary” exploring wildfire risk alongside practical, science-based responses, the film was screened privately as a proprietary work still in active circulation. The screening presented a detailed examination of causes, consequences, and management tools currently being applied in British Columbia and elsewhere, particularly in California.

Day three of the Truck Loggers Association convention opened with a private screening of BC Is Burning, a documentary produced by professional forester Murray Wilson that examines the province’s escalating wildfire crisis and the forest-management choices shaping its severity. Introduced by moderator Vaughn Palmer as an “urgent, powerful documentary” exploring wildfire risk alongside practical, science-based responses, the film was screened privately as a proprietary work still in active circulation. The screening presented a detailed examination of causes, consequences, and management tools currently being applied in British Columbia and elsewhere, particularly in California.

The film traces how BC’s wildfire seasons have intensified since 2017, noting that 7.4 million hectares have burned in that period—an area nearly two-and-a-half times the size of Vancouver Island. Through interviews with foresters, wildfire officials, scientists, and Indigenous practitioners, it links fire behaviour to accumulated forest fuels, insect damage, extended drought, and decades of fire suppression. Several speakers emphasize that while fire is a natural part of BC’s ecosystems, today’s fires are burning hotter, faster, and at scales that overwhelm suppression capacity. The film repeatedly returns to the argument that reacting to fires after ignition is no longer sufficient, and that fuel management is the only controllable variable among heat, wind, and ignition.

Much of the documentary focuses on forest condition. Veteran foresters describe overstocked stands, heavy surface fuels, ladder fuels that allow fires to climb into crowns, and landscapes altered by mountain pine beetle and spruce budworm. In several sequences, the consequences of high-intensity fires are shown directly, including sites where forest floor organic layers have been consumed, rocks fractured by heat, and soils altered by hydrophobic layers that repel water and increase erosion risk. Researchers explain that while above-ground biomass is often the focus of carbon accounting, soil carbon pools can equal or exceed it, and can be lost in hours during severe fires, taking decades or longer to rebuild.

Carbon is a recurring theme throughout the film. Scientists from Natural Resources Canada describe how wildfires have become one of BC’s largest and fastest-growing sources of greenhouse gas emissions, with direct fire emissions in recent years estimated at roughly double the province’s annual industrial emissions. The film challenges the assumption that forests function only as carbon sinks, noting that dead or burned forests stop absorbing carbon and can become long-term sources instead. By contrast, actively managed forests—through thinning, partial harvesting, regeneration harvesting, and replanting—are presented as a way to reduce fire intensity while maintaining long-term carbon storage in both forests and wood products.

Several management tools are examined in detail. Prescribed and cultural burning are shown as effective in reducing surface fuels, particularly when guided by Indigenous knowledge, though speakers acknowledge trade-offs related to smoke and emissions. Mechanical thinning and pruning near communities are presented as essential for creating defensible space, despite high costs and logistical challenges. In California, mastication and mechanized thinning are shown operating at scale, particularly in wildland–urban interface zones. The film contrasts these approaches with BC’s largely hand-based thinning programs, which are described as slow, labour-intensive, and expensive, often leaving removed material to be piled and burned due to the cost of hauling it out.

Harvesting is addressed directly as a fuel-reduction tool that also generates revenue, supports employment, and supplies material for wood products and bioenergy. Partial harvesting examples near Kamloops are shown where roughly half of the standing volume was removed, resulting in healthier crowns, improved regeneration, and reduced fire behaviour without eliminating visual or wildlife values. Regeneration harvesting is presented as a planned disturbance that creates age-class mosaics across landscapes, breaking up continuous fuels and reducing the likelihood of large, stand-replacing fires. Several speakers note that areas harvested and replanted decades ago often acted as buffers during recent wildfires, while adjacent unmanaged areas burned severely.

The documentary also contrasts BC’s situation with California’s response to catastrophic fire seasons earlier in the decade. California officials describe a shift away from a “leave it alone” mindset toward proactive management, supported by large-scale public funding, tribal partnerships, and coordinated planning across agencies. The film highlights California’s public tracking of treated hectares and the reopening of wood-processing capacity, including a new sawmill designed to utilize material from thinning and fire-damaged forests—material that would otherwise represent a disposal cost.

Following the screening, Palmer led a panel discussion with Dr., Research Scientist with Natural Resources Canada; Rob Schweitzer, Assistant Deputy Minister with the Ministry of Forests and BC Wildfire Service; and Jim McGrath, Natural Resources Manager with Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc. All three panelists also appeared in the film, allowing the discussion to build directly on perspectives presented during the screening. The discussion focused on how far BC has progressed toward the kind of landscape-scale management depicted in the documentary, and what remains unresolved.

Following the screening, Palmer led a panel discussion with Dr., Research Scientist with Natural Resources Canada; Rob Schweitzer, Assistant Deputy Minister with the Ministry of Forests and BC Wildfire Service; and Jim McGrath, Natural Resources Manager with Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc. All three panelists also appeared in the film, allowing the discussion to build directly on perspectives presented during the screening. The discussion focused on how far BC has progressed toward the kind of landscape-scale management depicted in the documentary, and what remains unresolved.

McGrath said that while progress has been made in parts of the Interior, policy and permitting delays are undermining both fire salvage harvesting and fuel mitigation. He cited examples where approvals took so long that fire-damaged wood lost economic value before it could be removed, eliminating opportunities to recover revenue, reduce fuels, and fund replanting. He also described operational barriers, including restrictions on pile burning near communities and equipment standards that prevent experienced contractors from participating in wildfire response. In his view, these constraints have driven treatment costs from roughly $3,500 per hectare in the past to as much as $10,000 per hectare today.

McGrath said that while progress has been made in parts of the Interior, policy and permitting delays are undermining both fire salvage harvesting and fuel mitigation. He cited examples where approvals took so long that fire-damaged wood lost economic value before it could be removed, eliminating opportunities to recover revenue, reduce fuels, and fund replanting. He also described operational barriers, including restrictions on pile burning near communities and equipment standards that prevent experienced contractors from participating in wildfire response. In his view, these constraints have driven treatment costs from roughly $3,500 per hectare in the past to as much as $10,000 per hectare today.

Schweitzer acknowledged that BC still has significant ground to cover and pointed to California as being 10 to 20 years ahead in terms of scale and integration. He emphasized that the province will not be able to suppress its way out of the problem, noting that extreme fire days can generate more ignitions than crews can realistically control. While prevention funding has increased, he said BC does not have the fiscal capacity to match California’s investment levels and will need a strong forest sector to help reduce fuel loads while supporting suppression and risk-reduction efforts.

Schweitzer acknowledged that BC still has significant ground to cover and pointed to California as being 10 to 20 years ahead in terms of scale and integration. He emphasized that the province will not be able to suppress its way out of the problem, noting that extreme fire days can generate more ignitions than crews can realistically control. While prevention funding has increased, he said BC does not have the fiscal capacity to match California’s investment levels and will need a strong forest sector to help reduce fuel loads while supporting suppression and risk-reduction efforts.

Smyth framed the challenge as both geographic and technical, noting that not all high-risk areas are accessible or suitable for the same treatments due to terrain, road access, or land-use constraints. She emphasized the need for mapping that links fire risk with feasible treatments, followed by economic analysis to determine costs and trade-offs. On public understanding, she noted that surveys conducted even after severe fire seasons show many people still view forests only as carbon sinks, underestimating the emissions released through fire and insect outbreaks.

Smyth framed the challenge as both geographic and technical, noting that not all high-risk areas are accessible or suitable for the same treatments due to terrain, road access, or land-use constraints. She emphasized the need for mapping that links fire risk with feasible treatments, followed by economic analysis to determine costs and trade-offs. On public understanding, she noted that surveys conducted even after severe fire seasons show many people still view forests only as carbon sinks, underestimating the emissions released through fire and insect outbreaks.

Panelists also discussed how to move the film’s message beyond industry audiences. Several noted that while forestry professionals may already accept the need for active management, broader public understanding remains uneven. The film itself was cited as an effective communication tool because it pairs problem definition with concrete examples of what works on the ground, rather than abstract policy debate. Wilson’s role as a forester rather than a filmmaker was noted, as was his intention to make the film more widely available once distribution costs are recovered.

Questions from the floor returned repeatedly to cost comparisons between prevention and suppression. Schweitzer noted that while prevention spending has increased, the scale of high-risk area—tens of millions of hectares—means funding alone cannot solve the problem. McGrath countered with examples where rapid salvage harvesting generated significant stumpage revenue and enabled successful reforestation, while delays turned similar areas into long-term liabilities. In his view, speed matters: breaking up hydrophobic soil layers, planting quickly, and restoring productivity can determine whether burned landscapes recover as forests or degrade into brush and grass.

Drafted with the assistance of digital tools to streamline the process.