Campbell River, British Columbia: La-kwa sa muqw Forestry Limited Partnership (LKSM) has been working to bring closure to the strike, which began on June 6, 2025, in a way that supports strong, positive, and enduring relationships between First Nations and other participants in the forestry sector in their territories and allows everyone to move forward together. Despite LKSM’s repeated efforts to achieve a negotiated resolution—including multiple applications for mediation and requests for special government intervention, the USW has continued to refuse both direct bargaining and third-party mediation. This now leaves legal action as the only available recourse to advance the interests of all parties and communities affected by the dispute. …This situation has left LKSM with no other option than to pursue a legal remedy that will remove this impediment to progress and enable resumption of negotiations.

Campbell River, British Columbia: La-kwa sa muqw Forestry Limited Partnership (LKSM) has been working to bring closure to the strike, which began on June 6, 2025, in a way that supports strong, positive, and enduring relationships between First Nations and other participants in the forestry sector in their territories and allows everyone to move forward together. Despite LKSM’s repeated efforts to achieve a negotiated resolution—including multiple applications for mediation and requests for special government intervention, the USW has continued to refuse both direct bargaining and third-party mediation. This now leaves legal action as the only available recourse to advance the interests of all parties and communities affected by the dispute. …This situation has left LKSM with no other option than to pursue a legal remedy that will remove this impediment to progress and enable resumption of negotiations.

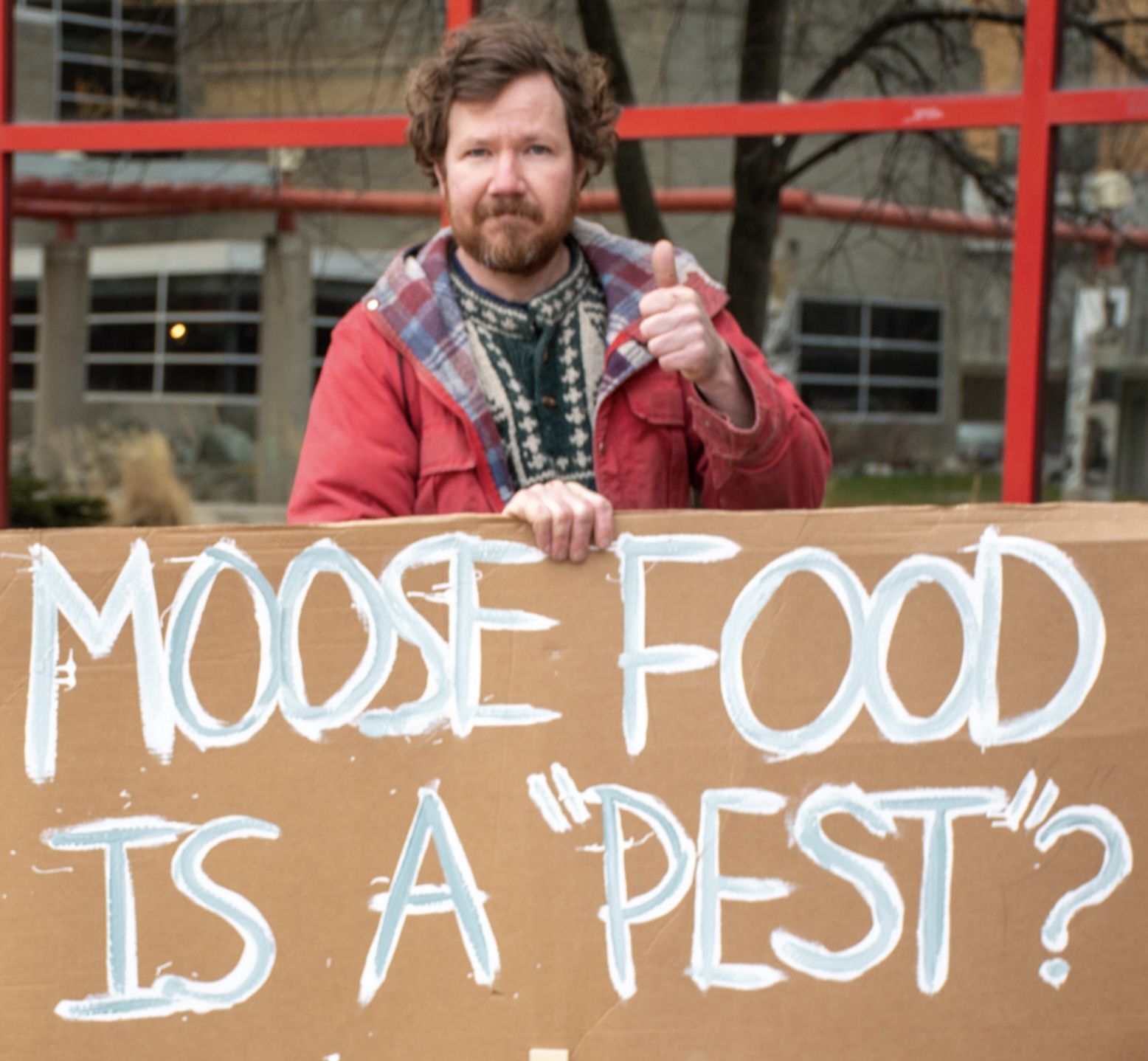

VANCOUVER ISLAND — Over 3 months later, 105 forestry workers are still on the picket lines this week after walking off the job June 6, and it doesn’t look like they expect to be going back to work anytime soon. …“I didn’t think we’d get to this point,” said United Steelworkers’ Jason Cox. …The union says the company wants to contract out jobs but La-kwa sa muqw Forestry says that’s not the case, it just wants to give new employees the choice. Operations manager Greg DeMille said, “They are demanding that we agree to mandatory union certification. And so with that and the fact we can’t agree to that because we feel it impacts employee’s rights to choose and has an impact to First Nations rights to free, prior and informed consent. …The union says it respects First Nation rights but insists this should be considered a “normal labour dispute” and nothing else.

VANCOUVER ISLAND — Over 3 months later, 105 forestry workers are still on the picket lines this week after walking off the job June 6, and it doesn’t look like they expect to be going back to work anytime soon. …“I didn’t think we’d get to this point,” said United Steelworkers’ Jason Cox. …The union says the company wants to contract out jobs but La-kwa sa muqw Forestry says that’s not the case, it just wants to give new employees the choice. Operations manager Greg DeMille said, “They are demanding that we agree to mandatory union certification. And so with that and the fact we can’t agree to that because we feel it impacts employee’s rights to choose and has an impact to First Nations rights to free, prior and informed consent. …The union says it respects First Nation rights but insists this should be considered a “normal labour dispute” and nothing else.

The BCIT School of Construction and the Environment offers two Associate Certificate programs designed to support workforce development in the North American lumber and sawmill sector:

The BCIT School of Construction and the Environment offers two Associate Certificate programs designed to support workforce development in the North American lumber and sawmill sector:

In this newsletter you’ll find these stories and more:

In this newsletter you’ll find these stories and more:

Mosaic Forest Management has clearly heard that communities value their outdoor access. After receiving what the company calls an “overwhelming” response to a survey, they will be moving forward with next steps on improving its recreation program. The survey garnered 7,600 responses in 23 days. “What we heard was clear. Communities value access to the outdoors and want more and better opportunities to do so,” said Mosaic’s CEO Duncan Davies (see report titled

Mosaic Forest Management has clearly heard that communities value their outdoor access. After receiving what the company calls an “overwhelming” response to a survey, they will be moving forward with next steps on improving its recreation program. The survey garnered 7,600 responses in 23 days. “What we heard was clear. Communities value access to the outdoors and want more and better opportunities to do so,” said Mosaic’s CEO Duncan Davies (see report titled

People should continue to use caution and take steps to be prepared by staying up to date on current conditions, following fire prohibitions and being Firesmart, as the risk of wildfire is expected to continue into fall. The BC Wildfire Service’s fall seasonal outlook forecasts ongoing wildfire risk for much of the province, especially in the Cariboo and southwestern Interior. Convective thunderstorms typically decrease as fall approaches; however, despite a lower likelihood of wildfires due to lightning, human-caused wildfires remain a risk. Until the southern coast shifts to a stormier fall-like pattern and the Prince George and Kamloops fire centres receive substantial rainfall, the wildfire danger ratings will continue to be elevated. As a result of the late summer’s record-breaking heat wave, combined with ongoing drought, people in B.C. are encouraged to be prepared for the risk of wildfire this fall.

People should continue to use caution and take steps to be prepared by staying up to date on current conditions, following fire prohibitions and being Firesmart, as the risk of wildfire is expected to continue into fall. The BC Wildfire Service’s fall seasonal outlook forecasts ongoing wildfire risk for much of the province, especially in the Cariboo and southwestern Interior. Convective thunderstorms typically decrease as fall approaches; however, despite a lower likelihood of wildfires due to lightning, human-caused wildfires remain a risk. Until the southern coast shifts to a stormier fall-like pattern and the Prince George and Kamloops fire centres receive substantial rainfall, the wildfire danger ratings will continue to be elevated. As a result of the late summer’s record-breaking heat wave, combined with ongoing drought, people in B.C. are encouraged to be prepared for the risk of wildfire this fall.

The District of 100 Mile House is refusing a proposed project that could see solar and wind farms built in the South Cariboo. During the Sept. 9 District of 100 Mile House Council meeting, around 50 people showed up to council to hear them deliberate about the Cariboo Wind and Solar Projects, which are a collection of wind and solar projects that are being proposed by MK Ince and Associates Ltd. …In a letter to the district, Tyrell Law, who is the current manager of the 100 Mile Community Forest, said that the project significantly overlaps with the Community Forest areas. The 100 Mile Community Forest is around 18,000 hectares in size and is managed by the 100 Mile Development Corporation. The proposal comprises around 730 hectares of the community forest. Law said that while Ince is partially correct to say that the area had been recently harvested and was in a plantation, it is more complicated than that.

The District of 100 Mile House is refusing a proposed project that could see solar and wind farms built in the South Cariboo. During the Sept. 9 District of 100 Mile House Council meeting, around 50 people showed up to council to hear them deliberate about the Cariboo Wind and Solar Projects, which are a collection of wind and solar projects that are being proposed by MK Ince and Associates Ltd. …In a letter to the district, Tyrell Law, who is the current manager of the 100 Mile Community Forest, said that the project significantly overlaps with the Community Forest areas. The 100 Mile Community Forest is around 18,000 hectares in size and is managed by the 100 Mile Development Corporation. The proposal comprises around 730 hectares of the community forest. Law said that while Ince is partially correct to say that the area had been recently harvested and was in a plantation, it is more complicated than that.

A shaggy, cool-green lichen hangs from the trunk of a tree in a forest on northeastern Vancouver Island. Lichenologist Trevor Goward has named it oldgrowth specklebelly. …Old-growth advocate Joshua Wright photographed oldgrowth specklebelly this summer in a forest about 400 kilometres northwest of Victoria. …Wright and Goward prize the forest in the Tsitika River watershed for its age and biodiversity, and a provincially appointed panel recommended that it be set aside from logging in 2021. But if a plan by the provincial logging agency, BC Timber Sales, goes ahead, the site will be auctioned for clearcut logging by the end of September. The area was stewarded by several Indigenous nations. …The plan to log it reveals differing opinions among Kwakwaka’wakw leaders on how to protect old-growth forests, while raising questions about which Aboriginal rights holders the BC government chooses to listen to, and why.

A shaggy, cool-green lichen hangs from the trunk of a tree in a forest on northeastern Vancouver Island. Lichenologist Trevor Goward has named it oldgrowth specklebelly. …Old-growth advocate Joshua Wright photographed oldgrowth specklebelly this summer in a forest about 400 kilometres northwest of Victoria. …Wright and Goward prize the forest in the Tsitika River watershed for its age and biodiversity, and a provincially appointed panel recommended that it be set aside from logging in 2021. But if a plan by the provincial logging agency, BC Timber Sales, goes ahead, the site will be auctioned for clearcut logging by the end of September. The area was stewarded by several Indigenous nations. …The plan to log it reveals differing opinions among Kwakwaka’wakw leaders on how to protect old-growth forests, while raising questions about which Aboriginal rights holders the BC government chooses to listen to, and why. Drought and wildfire have become the rule rather than the exception and that is bad news for wildlife, for fish, and for British Columbians who rely on healthy watersheds. …over the past couple of decades we drained wetlands, straightened streams, logged forests, built highways, and ripped millions of beavers from the landscape. The result is dry forests, destructive fire seasons, and choking smoke … every summer. Dry riverbeds are unable to support salmon populations, or any wildlife for that matter. A dewatered landscape is a towering forest of matchsticks waiting to burn. … So, how do we get from here to there? Fortunately, some of the answers are simple, natural, and inexpensive. …Prescribed and cultural burning helps restore native grassland and shrub-steppe ecosystems providing improved forage for large mammals. …BCWF’s 10,000 Wetlands Project has recently installed more than 100 beaver dam analogues and dozens of post-assisted log structures…

Drought and wildfire have become the rule rather than the exception and that is bad news for wildlife, for fish, and for British Columbians who rely on healthy watersheds. …over the past couple of decades we drained wetlands, straightened streams, logged forests, built highways, and ripped millions of beavers from the landscape. The result is dry forests, destructive fire seasons, and choking smoke … every summer. Dry riverbeds are unable to support salmon populations, or any wildlife for that matter. A dewatered landscape is a towering forest of matchsticks waiting to burn. … So, how do we get from here to there? Fortunately, some of the answers are simple, natural, and inexpensive. …Prescribed and cultural burning helps restore native grassland and shrub-steppe ecosystems providing improved forage for large mammals. …BCWF’s 10,000 Wetlands Project has recently installed more than 100 beaver dam analogues and dozens of post-assisted log structures… The Osoyoos Indian Band is kicking off its first commercial thinning silviculture treatment via Siya Forestry. In the project 28 kilometres northeast of Oliver, select trees will be harvested while the strongest will remain left to grow in the OIB First Nations woodland licence area. …Siya Forestry, the OIB-owned new company, said it aims to care for the land through stewardship, balance, and responsibility. “This is a great pilot project and hopefully it will lead to a bigger program within the Osoyoos Indian Band’s traditional territory,” said Luke Robertson, Siya Forestry, operations supervisor, in the press release.

The Osoyoos Indian Band is kicking off its first commercial thinning silviculture treatment via Siya Forestry. In the project 28 kilometres northeast of Oliver, select trees will be harvested while the strongest will remain left to grow in the OIB First Nations woodland licence area. …Siya Forestry, the OIB-owned new company, said it aims to care for the land through stewardship, balance, and responsibility. “This is a great pilot project and hopefully it will lead to a bigger program within the Osoyoos Indian Band’s traditional territory,” said Luke Robertson, Siya Forestry, operations supervisor, in the press release. The Coastal Fire Centre is lifting the campfire ban for the Campbell River, North Island and Sunshine Coast forest districts as of Sept. 17 at noon. Due to declining fire danger ratings on the northern part of Vancouver Island, the Province has chosen to re-allow campfires and other small fires in the area. Campfires will remain prohibited for the rest of the Coastal Fire Centre, with the exception of the Haida Gwaii Forest District. The activities that will be allowed also include the use of sky lanterns, wood-fired hot tubs, pizza ovens and other devices that are not vented through a flue or are incorporated into buildings. Category 2 and 3 open fires remain prohibited throughout the Coastal Fire Centre, which includes backyard burning, industrial burning, fireworks, burn barrels and burn cages. These restrictions will remain in place until 12:00 (noon), PDT, on Friday October 31, 2025, or until the order is rescinded.

The Coastal Fire Centre is lifting the campfire ban for the Campbell River, North Island and Sunshine Coast forest districts as of Sept. 17 at noon. Due to declining fire danger ratings on the northern part of Vancouver Island, the Province has chosen to re-allow campfires and other small fires in the area. Campfires will remain prohibited for the rest of the Coastal Fire Centre, with the exception of the Haida Gwaii Forest District. The activities that will be allowed also include the use of sky lanterns, wood-fired hot tubs, pizza ovens and other devices that are not vented through a flue or are incorporated into buildings. Category 2 and 3 open fires remain prohibited throughout the Coastal Fire Centre, which includes backyard burning, industrial burning, fireworks, burn barrels and burn cages. These restrictions will remain in place until 12:00 (noon), PDT, on Friday October 31, 2025, or until the order is rescinded.

First Nations in the North Cowichan region on Vancouver Island say a motion by the municipality is undermining collaborative efforts on the future of logging in the region’s forest reserve. …Cindy Daniels, chief of Cowichan Tribes, said the move by the council “undermines the collaborative nature” of work to date on a joint plan for the forest. …The North Cowichan council has been in discussions for a collaborative framework with Quw’utsun Nation since 2021 and announced a commitment to establish a co-management strategy for the forest reserve in April 2024. …Gary Merkel, director of the Centre for Indigenous Land Stewardship at UBC…. “It’s a little bit ahead of itself that motion, but not too far. I mean, they haven’t said ‘we’re just going to go and log,’ they’ve allowed the possibility”. …”We are going to get a staff report outlining some of the implications and next steps,” North Cowichan Mayor Rob Douglas said.

First Nations in the North Cowichan region on Vancouver Island say a motion by the municipality is undermining collaborative efforts on the future of logging in the region’s forest reserve. …Cindy Daniels, chief of Cowichan Tribes, said the move by the council “undermines the collaborative nature” of work to date on a joint plan for the forest. …The North Cowichan council has been in discussions for a collaborative framework with Quw’utsun Nation since 2021 and announced a commitment to establish a co-management strategy for the forest reserve in April 2024. …Gary Merkel, director of the Centre for Indigenous Land Stewardship at UBC…. “It’s a little bit ahead of itself that motion, but not too far. I mean, they haven’t said ‘we’re just going to go and log,’ they’ve allowed the possibility”. …”We are going to get a staff report outlining some of the implications and next steps,” North Cowichan Mayor Rob Douglas said.

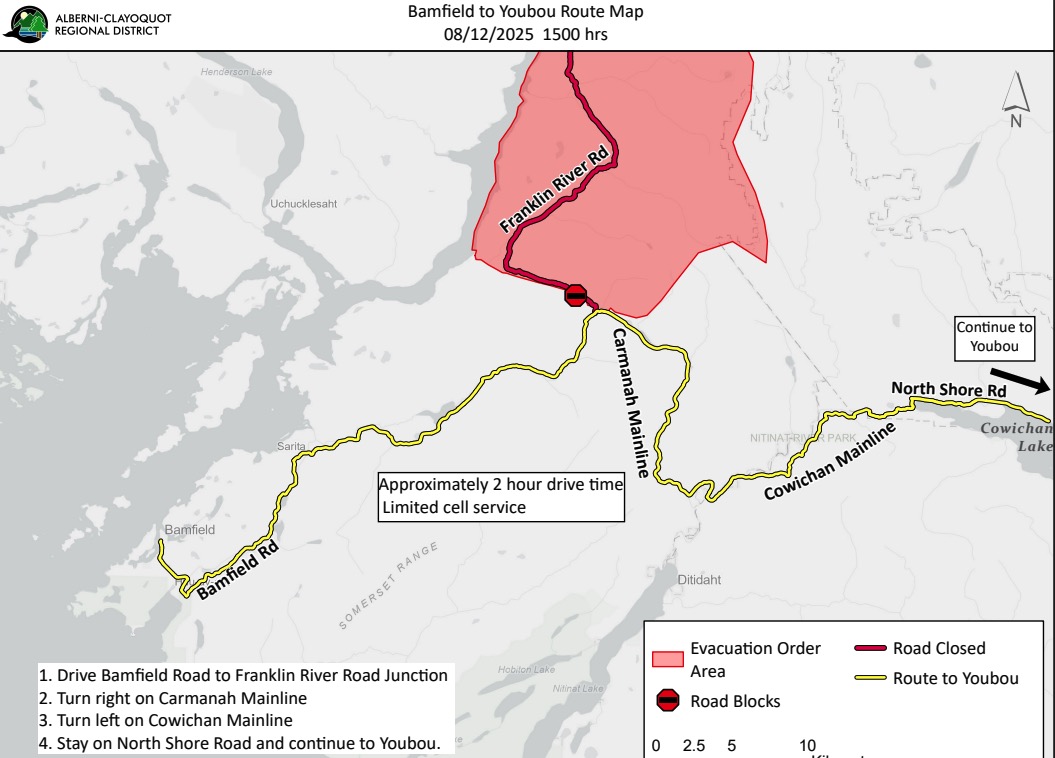

The fire-ravaged Bamfield Main Road, which connects Bamfield and several First Nation communities to Port Alberni, will reopen by the end of October, the Transportation Ministry announced. The ministry said temporary closures could still occur, however, during periods of heavy rain and strong winds. It said a geotechnical assessment to identify hazards, and assessments of the stability of trees are ongoing. Based on those findings, thresholds are being established for wind and rain events that will trigger increased patrols of Bamfield Main and potentially closures. A weather station and closure gates will be installed in the coming weeks, according to the ministry, which is leading efforts to reopen the road with Mosaic Forest Management, the company that oversees the affected stretch. …Ditidaht Nation Chief Judi Thomas said she suspects the Alberni-Clayoquot Regional District, Huu-ay-aht First Nation and Mosaic and Bamfield would be more than happy to support a provincial paved alternate route.

The fire-ravaged Bamfield Main Road, which connects Bamfield and several First Nation communities to Port Alberni, will reopen by the end of October, the Transportation Ministry announced. The ministry said temporary closures could still occur, however, during periods of heavy rain and strong winds. It said a geotechnical assessment to identify hazards, and assessments of the stability of trees are ongoing. Based on those findings, thresholds are being established for wind and rain events that will trigger increased patrols of Bamfield Main and potentially closures. A weather station and closure gates will be installed in the coming weeks, according to the ministry, which is leading efforts to reopen the road with Mosaic Forest Management, the company that oversees the affected stretch. …Ditidaht Nation Chief Judi Thomas said she suspects the Alberni-Clayoquot Regional District, Huu-ay-aht First Nation and Mosaic and Bamfield would be more than happy to support a provincial paved alternate route. On September 11, 2025, UBC’s Faculty of Forestry welcomed British Columbia’s Minister of Forests, Ravi Parmar, to the Malcolm Knapp Research Forest (MKRF) to witness the critical work being done to advance sustainable forest management and educate the next generation of foresters. The tour, led by Dr. Dominik Roeser, Associate Dean of Research Forests and Community Outreach, and joined by Dr. Robert Kozak, Professor and Dean of the Faculty of Forestry and Hélène Marcoux, Malcolm Knapp Research Forest Manager, provided an important opportunity to showcase MKRF’s role in bridging scientific research, education and practical forest management. Minister Parmar’s visit included important conversations focused on forest stewardship and the role research plays, not just in understanding forests, but also in driving innovation, education, and creating future opportunities. Minister Parmar was able to see firsthand the vital research taking place to support both industry and government, and the advancement of sustainable forest management practices in British Columbia.

On September 11, 2025, UBC’s Faculty of Forestry welcomed British Columbia’s Minister of Forests, Ravi Parmar, to the Malcolm Knapp Research Forest (MKRF) to witness the critical work being done to advance sustainable forest management and educate the next generation of foresters. The tour, led by Dr. Dominik Roeser, Associate Dean of Research Forests and Community Outreach, and joined by Dr. Robert Kozak, Professor and Dean of the Faculty of Forestry and Hélène Marcoux, Malcolm Knapp Research Forest Manager, provided an important opportunity to showcase MKRF’s role in bridging scientific research, education and practical forest management. Minister Parmar’s visit included important conversations focused on forest stewardship and the role research plays, not just in understanding forests, but also in driving innovation, education, and creating future opportunities. Minister Parmar was able to see firsthand the vital research taking place to support both industry and government, and the advancement of sustainable forest management practices in British Columbia. The ancient forests near Fairy Creek, where the largest act of civil disobedience in Canadian history took place in 2021, have been fairly silent for nearly four years. But as logging in Vancouver Island’s old-growth forests picks up, protesters have returned to protect these ancient trees. On Friday, BC Supreme Court judge Amy Francis approved an injunction requested by Tsawak-qin Forestry Inc.—co-owned by Western Forest Products and the Huu-ay-aht First Nations—after two days of hearings. Those named in the injunction—including Elder Bill Jones…are banned from blocking the logging company’s access to old-growth forests in the Tree Farm License 44 area. …The removal of the sculpture and the people protesting could happen at any time. Today, blockaders at Cougar Camp—named for the sculpture blocking the logging road—said they were ready and waiting to be arrested while protecting Upper Walbran.

The ancient forests near Fairy Creek, where the largest act of civil disobedience in Canadian history took place in 2021, have been fairly silent for nearly four years. But as logging in Vancouver Island’s old-growth forests picks up, protesters have returned to protect these ancient trees. On Friday, BC Supreme Court judge Amy Francis approved an injunction requested by Tsawak-qin Forestry Inc.—co-owned by Western Forest Products and the Huu-ay-aht First Nations—after two days of hearings. Those named in the injunction—including Elder Bill Jones…are banned from blocking the logging company’s access to old-growth forests in the Tree Farm License 44 area. …The removal of the sculpture and the people protesting could happen at any time. Today, blockaders at Cougar Camp—named for the sculpture blocking the logging road—said they were ready and waiting to be arrested while protecting Upper Walbran.  Zoom Presentation

Zoom Presentation

A B.C. Supreme Court justice has ordered a group of people blocking a logging road in the Walbran Valley on southern Vancouver Island to stop. The decision to grant an injunction to Tsawak-qin Forestry Limited Partnership, a joint partnership between the Huu-ay-aht First Nations and Western Forest Products, alongside an enforcement order is expected to set the stage for the RCMP to remove people from the area. This fight over British Columbia’s old-growth forests comes four years after the start of the historic Fairy Creek protests, where more than 1,100 people were arrested. The Walbran Valley blockade began in late August and has prevented a logging company from working and accessing tools, equipment and vehicles on the other side of the blockade. Pacheedaht Elder Bill Jones, who was at the forefront of the Fairy Creek protests, is one of the parties named in the court filing, and the only person to respond to the application.

A B.C. Supreme Court justice has ordered a group of people blocking a logging road in the Walbran Valley on southern Vancouver Island to stop. The decision to grant an injunction to Tsawak-qin Forestry Limited Partnership, a joint partnership between the Huu-ay-aht First Nations and Western Forest Products, alongside an enforcement order is expected to set the stage for the RCMP to remove people from the area. This fight over British Columbia’s old-growth forests comes four years after the start of the historic Fairy Creek protests, where more than 1,100 people were arrested. The Walbran Valley blockade began in late August and has prevented a logging company from working and accessing tools, equipment and vehicles on the other side of the blockade. Pacheedaht Elder Bill Jones, who was at the forefront of the Fairy Creek protests, is one of the parties named in the court filing, and the only person to respond to the application.

As summer winds down, I’m pleased to welcome you to this special edition of the Forest Practices Board’s newsletter. This season marks a significant milestone for us—our 30th anniversary. For three decades, the Board has worked diligently to provide independent oversight of forest and range practices in British Columbia, helping to ensure that our natural resources are managed sustainably and in the public interest. …This issue highlights some of the conversations, initiatives, audits, investigations and special reports the Board is involved in as we embark on this anniversary year.

As summer winds down, I’m pleased to welcome you to this special edition of the Forest Practices Board’s newsletter. This season marks a significant milestone for us—our 30th anniversary. For three decades, the Board has worked diligently to provide independent oversight of forest and range practices in British Columbia, helping to ensure that our natural resources are managed sustainably and in the public interest. …This issue highlights some of the conversations, initiatives, audits, investigations and special reports the Board is involved in as we embark on this anniversary year.

The Cariboo Wood Innovation Training Hub (CWITH) is inviting people to bring their ideas and opinions to an upcoming workshop on contemplative forestry. The workshop will be facilitated by Jason Brown, an affiliate forest professional with Forest Professionals British Columbia, on Saturday, Sept. 20. Participants will explore the concept of contemplative forestry, an approach which meets two extreme views on forestry in the middle. …Stephanie Huska, project lead with CWITH, said the workshop is a way to open the door to conversations which historically have not been included in natural resource management discussions based on western worldviews. …A contemplative approach to forest management values manual work as a form of spiritual practice, allows forests to ‘speak’ for themselves, admits there are some aspects of life we don’t have the language for and sees forestry as a mutually beneficial, place-based vocation.

The Cariboo Wood Innovation Training Hub (CWITH) is inviting people to bring their ideas and opinions to an upcoming workshop on contemplative forestry. The workshop will be facilitated by Jason Brown, an affiliate forest professional with Forest Professionals British Columbia, on Saturday, Sept. 20. Participants will explore the concept of contemplative forestry, an approach which meets two extreme views on forestry in the middle. …Stephanie Huska, project lead with CWITH, said the workshop is a way to open the door to conversations which historically have not been included in natural resource management discussions based on western worldviews. …A contemplative approach to forest management values manual work as a form of spiritual practice, allows forests to ‘speak’ for themselves, admits there are some aspects of life we don’t have the language for and sees forestry as a mutually beneficial, place-based vocation.

VANCOUVER — The B.C. Supreme Court is set to rule on an injunction to halt a blockade against old-growth logging in the Walbran Valley on Vancouver Island, but a lawyer for one of the blockaders says the law is evolving and in need of a “course correction.” The Pacheedaht First Nation has decried the blockade on its traditional territory near Port Renfrew, B.C., claiming it is undermining its authority and should disband. The First Nation said in a statement that forestry is a “cornerstone” of its economy, and is calling for the blockaders to “stand down and leave.” The statement came after Tsawak-qin Forestry Inc., a firm co-owned by the Huu-ay-aht First Nations and Western Forest Products Inc., filed a lawsuit last week in B.C. Supreme Court alleging that “a group of largely unknown individuals” began the blockade of a road on Aug. 25.

VANCOUVER — The B.C. Supreme Court is set to rule on an injunction to halt a blockade against old-growth logging in the Walbran Valley on Vancouver Island, but a lawyer for one of the blockaders says the law is evolving and in need of a “course correction.” The Pacheedaht First Nation has decried the blockade on its traditional territory near Port Renfrew, B.C., claiming it is undermining its authority and should disband. The First Nation said in a statement that forestry is a “cornerstone” of its economy, and is calling for the blockaders to “stand down and leave.” The statement came after Tsawak-qin Forestry Inc., a firm co-owned by the Huu-ay-aht First Nations and Western Forest Products Inc., filed a lawsuit last week in B.C. Supreme Court alleging that “a group of largely unknown individuals” began the blockade of a road on Aug. 25. Provincial investigators looking into the cause of this spring’s wildfire near Lynn Lake, Man., allege it started at the nearby Alamos Gold Inc. mining site and that the company was negligent because it didn’t use water to extinguish its burn piles, according to search warrant documents obtained by CBC News. Manitoba Conservation investigators allege the fire, which eventually grew to over 85,000 hectares, started on May 7 after a burn pile reignited at the Toronto-based gold producer’s MacLellan mine site, about 7.5 kilometres northeast of Lynn Lake. By late May, the fire had come within five kilometres of Lynn Lake and forced the evacuation of the nearly 600 residents of the town… Dozens of properties in the area were destroyed. …The investigators asked Alamos Gold staff how they ensured the burn piles were extinguished. The workers said they stirred the piles and installed a fire guard around them, according to the documents.

Provincial investigators looking into the cause of this spring’s wildfire near Lynn Lake, Man., allege it started at the nearby Alamos Gold Inc. mining site and that the company was negligent because it didn’t use water to extinguish its burn piles, according to search warrant documents obtained by CBC News. Manitoba Conservation investigators allege the fire, which eventually grew to over 85,000 hectares, started on May 7 after a burn pile reignited at the Toronto-based gold producer’s MacLellan mine site, about 7.5 kilometres northeast of Lynn Lake. By late May, the fire had come within five kilometres of Lynn Lake and forced the evacuation of the nearly 600 residents of the town… Dozens of properties in the area were destroyed. …The investigators asked Alamos Gold staff how they ensured the burn piles were extinguished. The workers said they stirred the piles and installed a fire guard around them, according to the documents.