Kevin Mason

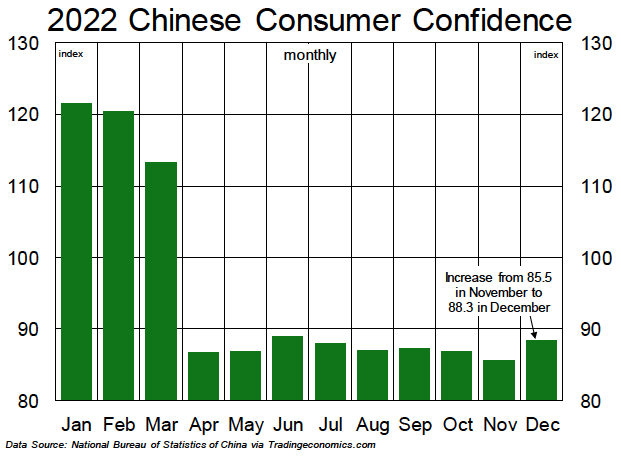

We are already two months into 2023, yet it feels as if we are still holding our breath to understand the general direction of the year ahead. One of the largest drivers in our space will be China’s appetite for commodities as the country exits its COVID-lockdown era. We have had a few early, contradictory indicators so far. For one, commodity dissolving pulp prices jumped up in February on higher operating rates and optimism about an increase in textile demand as Chinese consumers exit stuck-at-home mode; in contrast, Nine Dragons has announced extensive downtime at its domestic Chinese packaging operations due to soft demand—hardly a harbinger of amped-up commodity demand in first half 2023. Some very challenging conditions for the Chinese economy persist, including the real estate slowdown, with real estate land acquisition down 53% y/y in 2022.

The largest overhang, however, is likely the geopolitical situation, with China’s relationship with Russia driving fears of potential Western trade sanctions and contributing to very cautious consumer sentiment. A robust reopening would drive a better year for pulp producers (benefiting Mercer, Canfor Pulp and others directly, and all pulp producers indirectly), improvements for packaging producers (through more exports from North America and a tighter domestic market), and stronger timber prices/exports for the Pacific Northwest and New Zealand. General second-order effects would be even greater. The path forward remains unclear at this point, but few drivers will have a greater impact on our space in 2023.

The largest overhang, however, is likely the geopolitical situation, with China’s relationship with Russia driving fears of potential Western trade sanctions and contributing to very cautious consumer sentiment. A robust reopening would drive a better year for pulp producers (benefiting Mercer, Canfor Pulp and others directly, and all pulp producers indirectly), improvements for packaging producers (through more exports from North America and a tighter domestic market), and stronger timber prices/exports for the Pacific Northwest and New Zealand. General second-order effects would be even greater. The path forward remains unclear at this point, but few drivers will have a greater impact on our space in 2023.

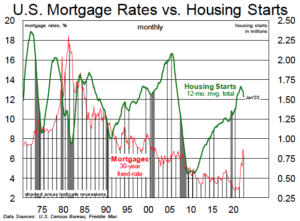

Another big macroeconomic wild card for 2023 is what happens with the Fed funds rate. We have seen expectations around U.S. monetary policy flip-flop several times already this year, but stubbornly high inflation and blockbuster job numbers for January now suggest the Fed could continue hiking through the middle of the year (the market is pricing in a terminal rate of 5.5%), and the next rate-cut cycle may not begin until 2024. This would delay a recovery in housing; the most obvious impacts would be felt by solid-wood names, with second-order effects on timber REITs and pulp producers.

Another big macroeconomic wild card for 2023 is what happens with the Fed funds rate. We have seen expectations around U.S. monetary policy flip-flop several times already this year, but stubbornly high inflation and blockbuster job numbers for January now suggest the Fed could continue hiking through the middle of the year (the market is pricing in a terminal rate of 5.5%), and the next rate-cut cycle may not begin until 2024. This would delay a recovery in housing; the most obvious impacts would be felt by solid-wood names, with second-order effects on timber REITs and pulp producers.

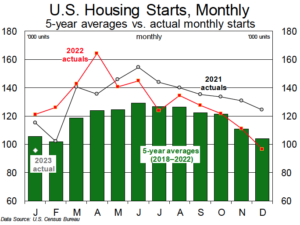

Sentiment around the broader housing market has flip-flopped in recent months. In January there was a growing feeling that earlier pessimism on the 2023 outlook was overblown (we had seen housing start forecasts as low as 1.0MM units!) and that the downturn in housing could be shorter and shallower than previously expected. However, there was little in January housing data to suggest that a bottom is anywhere near, and our forecast for 2023 starts is unchanged at 1.3MM units (with a downward bias).

Sentiment around the broader housing market has flip-flopped in recent months. In January there was a growing feeling that earlier pessimism on the 2023 outlook was overblown (we had seen housing start forecasts as low as 1.0MM units!) and that the downturn in housing could be shorter and shallower than previously expected. However, there was little in January housing data to suggest that a bottom is anywhere near, and our forecast for 2023 starts is unchanged at 1.3MM units (with a downward bias).

U.S. housing starts slipped to a seasonally adjusted 1.31MM units in January—well below economists’ consensus of 1.35MM—as widespread inclement weather caused major disruptions in several key building states. December’s starts were revised lower to an adjusted 1.37MM units (bringing the full-year 2022 total to 1.55MM). Seasonally adjusted permits were virtually unchanged m/m at 1.34MM, with single-family permissions off ~2% m/m and a shocking 40% y/y, while multifamily permits were up ~2% m/m to an adjusted 621,000 units.

Home sales data were a mixed bag in January, with new-home sales impressive and existing-home sales setting a 12-year low. Sales of new homes climbed to a 10-month high in January, increasing by over 7% m/m to an adjusted 670,000 units. A reduction in mortgage rates around the turn of the year likely contributed to the improvement, but an uptick in rates over the past month will raise questions about the staying power of this recovery. For existing homes, sales slumped to their lowest level in over 12 years in January (an adjusted 4.0MM units, down ~1% m/m and fully ~37% y/y) and have now posted declines for 12 consecutive months. Housing bulls will point to the slowing rate of decline as cause for optimism here, but we are less convinced.

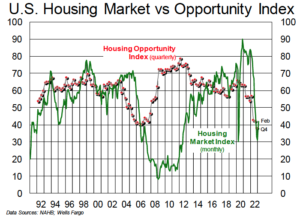

Around the end of last year, there was little optimism in the market and most were bracing for a very challenging 2023. However, by January, the outlook was decidedly less bearish, perhaps buoyed by chatter of a lower (5.0%?) terminal Fed rate and the possibility of the first rate cut around mid-year. The NAHB/Wells Fargo HMI posted an increase in January (arresting 12 consecutive monthly declines) and a second increase followed in February, with the reading improving from 35 to 42 but down from 81 a year ago (note that a reading under 50 indicates that more builders view market conditions as poor than good).

Around the end of last year, there was little optimism in the market and most were bracing for a very challenging 2023. However, by January, the outlook was decidedly less bearish, perhaps buoyed by chatter of a lower (5.0%?) terminal Fed rate and the possibility of the first rate cut around mid-year. The NAHB/Wells Fargo HMI posted an increase in January (arresting 12 consecutive monthly declines) and a second increase followed in February, with the reading improving from 35 to 42 but down from 81 a year ago (note that a reading under 50 indicates that more builders view market conditions as poor than good).

However, that optimism didn’t last too long. Commentary on Q4 earnings calls was quite sobering, and, with sticky January inflation numbers and a more hawkish tone in the latest Fed meeting minutes, it feels like we are back at square one—with at least another couple of quarters of weak housing demand seemingly assured. In the near-term, we expect recent increases in U.S. mortgage rates to put a chill on housing starts (we saw this happen when rates ran up in Q4/22). The 30-year rate has increased in each of the last three weeks and currently sits at 6.50% (up 41bps over that period). Unsurprisingly, mortgage applications have moved in the opposite direction, decreasing in each of the last two weeks, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association.

After two-plus years of heightened volatility around the pandemic (commodities, stock market and housing were all impacted), it is perhaps understandable that minor changes in underlying data often garner an outsized (over)reaction. However, we have seen little concrete evidence to date that suggests 2023 will be anything but a highly challenging year for commodities and companies with exposure to the U.S. housing market.